Down East Magazine

SEPTEMBER 1971

Ivan Flye Studio.

By J. Malcolm Barter

From Down East Magazine’s September 1971 issue.

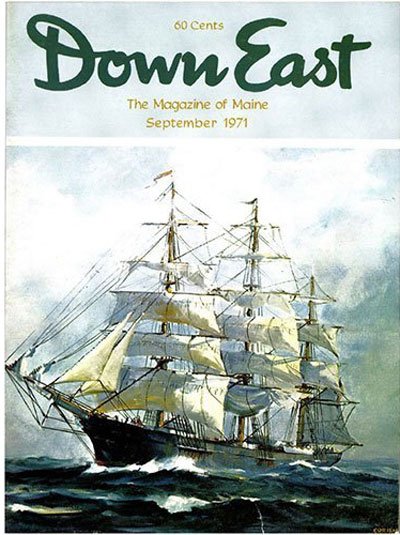

The cover of the September 1971 issue : “Running Before The Trades” by Joseph R. Corish.

At age thirty, David Hanna of Round Pond, Maine is something of a marvel in the modern-day art world. The son of a coal miner, he never went to art school, never took a formal art lesson and did his first serious painting only seven years ago, because his wife said she would like a picture to hang on the bare wall in their apartment in a Pittsburgh housing project. Yet since that time he has produced 700 watercolors, tempera and dry brush paintings that have been eagerly bought by collectors at twenty-four one-man exhibits across the country. There he has been acclaimed as one of America’s foremost young realist painters in the tradition of Howard Pyle and N. C. and Andrew Wyeth. Ironically, although he has lived and worked in Maine for four years, no exhibit of his work has yet been held here, and until recently the heads of three Maine art galleries and a professor of art at one of Maine’s colleges never had heard of him.

David Hanna calls himself “a painter who hopes someday to be an artist” in all media, including sculpture, in which he has just begun to work. If the rigid schedule of self-training and continuous production he has set for himself are any indication of that determination, his goal is not far distant. Already money he has earned from commissioned works and from sales at exhibits has enabled him to build a spacious new home at Moxie Cove, Round Pond, overlooking Muscongus Sound and Loud’s Island. The eleven-room house, which is modeled after the Parson Capen House in Topsfield, Massachusetts, contains several pieces of antique furniture, carefully selected and beautifully restored by David and his family. Hanna prides himself on his craftsmanship, which is as visible in the cabinetry and stonework he has done around his home as it is in the infinite detail of his paintings.

A slim, wiry, dark-haired man, David Hanna has the intense dedication of a young boxer who has fought his way up to the semi-finals and is in peak training for the championship bout. Smart money in the art world is betting on him as a sure thing to win.

Sketch pad in hand, David explores the secluded coves and back roads of the Pemaquid peninsula, capturing scenes and ideas for his paintings, which he often creates late at night after his family has gone to bed. The subject he chooses may be a stump or a rock deep in the woods, a derelict boat on the shore, an abandoned farm building or a seagull lying dead on the beach. Two of his Maine scenes are in a portfolio of full-color reproductions published exclusively for Abercrombie & Fitch by Great American Editions Ltd., 111 East 80th Street, New York City. “The Meeting Place” portrays light coming through a recessed window onto the seat of a pew in the old Harrington Meeting House at Pemaquid. “Low Tide at Damariscotta” shows the hulk of the schooner Lois M. Candage, her masts still standing, on the shore at Damariscotta. When making a sketch for this painting David crawled under the pilings of a wharf on the waterfront in order to obtain the perspective he wanted of the old coaster.

The Hannas’ four daughters and small son — Cory 11, Tammy 9, Lisa 8, Jamie 7, and David 4 — often figure in their father’s paintings. He has a special knack and a fondness for doing pictures of children, and much of his portrait commission work is of young boys and girls. One of the works he refuses to sell — it hangs on his dining room wall — is a large drawing of his boy Davey and elderly Alexander Breede, a former sailor and Monhegan artist who was once a neighbor of the Hannas at Pemaquid Light. The work has an enchanting quality, enhanced by meticulous attention to arrangement and detail, especially in the old man’s slim hand resting on the arm of the chair. A Pennsylvania orthopedic surgeon, Dr. John Inghram, who has purchased several of Hanna’s paintings, schooled the young artist in anatomy so that the figures he paints have proper muscle and bone.

Clockwise: David Hanna and his family (Ivan Flye Studio); “The Meeting Place”; “Low Tide at Damariscotta” (Levers’ Studio)

Maine neighbors call David Hanna “a worker.” He personifies the word. “My hobby,” he says, “is work.” It shows in what he has done with his own hands to help build and decorate his new home, in the quantity as well as the quality of his paintings, and in his plans for the future. He has another nationwide tour of exhibits scheduled for this fall. Then he hopes to spend a year in Europe with his family, studying the techniques of old world artists under the tutelage of the curator of restoration at the Louvre. “If you stop learning, you stop growing,” is the way he explains such drive.

Meanwhile he will continue to teach himself the art of sculpture, producing tiny figures in clay that will be cast in bronze or silver. A figurine of a Roman gladiator rested on a revolving pedestal on the table, and he occasionally gave it a spin as he emphasized a point.

Art had no place in the family into which David Hanna was born in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania on August 31, 1941, the youngest of twelve children, five of them by previous marriages of his father and mother. His father, Harry Hanna, had worked in the coal fields of Pennsylvania and Kentucky and later became a machinist and metal moulder. He was robbed and killed by street hoodlums in 1963, but David’s mother still lives in Pittsburgh.

There were few luxuries thirty years ago in the Hanna household, which moved between Pittsburgh and Ashland, Kentucky. By the time David was eleven he was working long hours in a gas station and doing whatever odd jobs he could find. At fourteen, after completing the eighth grade, he quit school — not because he couldn’t do the classwork, but because he was not psychologically adapted to school. He needed to get out, make his own way and break the pattern of existence in which he felt trapped.

For a while he worked even longer hours in a gas station, then got a job with a dancing school, interviewing prospective pupils and also helping out as a teaching partner on the dance floor. From dancing he went into acting. He was with the Caramo Playhouse in Cleveland, Ohio before moving to Los Angeles to do commercials and small daytime performances with a television station, He was only sixteen, but misrepresented his age to get the job.

In 1960, age eighteen, he married Carol Elco, a girl of Russian extraction from Donora, Pennsylvania. She is a friendly, blonde woman who gives the outward appearance of marveling at her genius of a husband, yet all the while understanding him to a “t”.

Clockwise: “Decoy”; “At Pemaquid, 1969”; “Shell Heaps”

The young couple’s early days together were cut short by the war in Southeast Asia. Within a few months of their marriage David was off for thirty-nine months service as a weapons expert with the 82nd Airborne and the Green Berets, first in Laos and later in South Vietnam. He feels today that if American forces remain in Southeast Asia, they should fight the Viet Cong with guerrilla tactics, similar to those used successfully by the British in Malaysia.

While serving with the 82nd Airborne, David returned to Washington in January, 1961 as part of the honor guard at the inauguration of President John F. Kennedy. Three years later he was out of uniform and back in Pittsburgh, selling insurance. While in the armed forces he had obtained the equivalent of a high school diploma and in Pittsburgh began taking evening courses at Point Park Junior College with hopes of entering Carnegie Tech.

His interest in painting might be traced to a wartime visit to Hong Kong with his friend Tony Scott, a jazz clarinet player. There he saw an abstract painting and, “just as a lark,” produced a parody of it. But not until 1964, after he and Carol had moved into a housing project in Pittsburgh, did he do what he calls his first painting of his own.

“Carol said she’d like a painting for the wall of our living room. So I took some Kemtone paint and a ten-cent watercolor set and did her a scene of Williamsburg, Virginia. It was a small russet-colored painting about 12 by 14 inches.”

When Jack Dougherty, manager of the housing project, saw the painting hanging on the Hannas’ wall, he asked David to do one for him — a larger landscape in oil. “He liked it so much,” David tells, “that he paid me $250. It was my first commission.”

From top: Alexander Breed and Davey Hanna; Yacht America at Boothbay (Nathan Rabin).

Dougherty also passed word to the people at the Pittsburgh Playhouse, who were planning an amateur art show in the playhouse restaurant, that he had a young artist living in his project who was “pretty good.” David was invited to contribute and did fifteen landscapes and two portraits. All but two sold the first day of the show.

“Wouldn’t it be great,” David told his wife, “if I could just paint and earn $100 a week? That was what I had been Iooking for all my life — a chance to express myself.”

Following the playhouse art show, reports of Hanna’s talent reached the attention of the family of the late R. M. Mellon, millionaire art collector of Ligonier, Pennsylvania, resulting in a commission for a landscape and an exhibit of David’s work at the Mellon estate, “Rolling Rock.” As a result, Hanna and his wife were able to move out of the Pittsburgh housing project to a small house in Chester County, Pennsylvania, homeground of the Brandywine school of painters. There David began painting full-time.

Two years later he moved to Bristol, Maine. Bristol is full of Hannas, but David is no relation. He came to Maine, he explains, because he likes the sea and the closeness Maine people have with their surroundings. At first he rented the old lightkeeper’s dwelling next to the lighthouse at Pemaquid Point. He left only to accompany his exhibits around the country or for an occasional trip to Florida or Europe. He found Lands End in Cornwall, England much like the Maine coast.

The Hannas built their new home and moved into it last year. It is situated among oaks and spruces at the end of a dirt road, a mile from Route 32. It lies so far off the beaten track that Mrs. Hanna has to drive the older children out to meet the school bus and pick them up when the bus drops them off at the Moxie Cove Road after school. The house, built of brick and wood with heavy exposed oak beams in the ceilings and wide, pegged oak planking on the floors, seems to go with Hanna’s style of painting. Wood is emphasized throughout, as in many of his temperas and watercolors.

“Wood,” he says, “has texture and density and is familiar to most people. They feel at home with it; it reminds them of some place they know. I try to paint it that way.” It is the same with his rocks and trees and the people in his portraits. They, too, seem real, but with an extra, special quality. David Hanna calls it the “magic of realism.”

Left to right: New Harbor, 1969; South Bristol, 1969.

The tendency of art critics to compare David Hanna’s work to that of Andrew Wyeth is understandable. Both are realist painters in the Brandywine tradition, begun a century ago by the renowned artist-illustrator-author Howard Pyle and perpetuated by such noted disciples as Frank Schoonover, Maxfield Parrish, Stanley Arthurs, Jessie Wilcox Smith, and N. C. Wyeth, father of Andrew. Both Andrew Wyeth and David Hanna often paint similar subjects — the stark, weather-beaten building, the open door or window, as well as portraits of old men with craggy faces and distant looking blue eyes. Both artists have lived and worked in Chester County, Pennsylvania and on the coast of Maine. The familiar Wyeth land of Cushing and the Christina Olson Farm Iies only a few miles east of Round Pond across Muscongus Bay. David has made a pilgrimage there, met Christina and her brothers Alvaro and Sam and done several paintings of the outside of the Olson Farm.

The younger painter admits that he so admires Wyeth’s work and skill that he deliberately moved to Chester County in order to familiarize himself with some of the scenes that helped make the older artist famous. One of David’s earliest attempts at painting was a practice copy he made from a colored photo in Time magazine of Wyeth’s “Trodden Weed,” showing a pair of cavalier boots beneath a black cloak.

David Hanna recognizes “Mr. Wyeth” — he always calls him “Mister —” as the “master of realist painting and our greatest living artist.” Yet he studiously avoids the charge of copying him. When he learned, for example, that Andrew Wyeth had done a painting of the lightkeeper’s dwelling at Pemaquid Point, he declined to do one himself, even though he wanted a memento of the days he and his family lived there.

“A Million Miles Away, 1970″.